Global crises require bold and comprehensive policy responses. This has been the case after the Global Crisis of 2008-09, and it is certainly the case in the current COVID-19 crisis.

Clearly, the two crises differ. The Global Crisis was rooted in vulnerabilities in the global financial system, which spilled over into the real economy. The COVID-19 crisis is a global health shock which, together with the containment measures, imposes a severe shock on the real economy and threatens to impair the stability of the financial system.

Consequently, the policy responses have differed. In 2009, G20 policy leaders agreed on a comprehensive package of financial sector reforms. The aim since then has been to build resilient financial institutions, to end ‘too big to fail’, to make derivatives markets safer, and to enhance the resilience of non-bank financial intermediation (NBFI). In 2020, governments, central banks, and regulators around the globe engaged in massive programmes to support the liquidity and solvency of the real economy and the financial system. European leaders have taken bold steps towards fending off the corona shock and supporting the European economy and common market. Together with the enhanced robustness of the financial system, these decisive policy measures have so far prevented the spillover of the corona shock to the financial system.

Notwithstanding these differences, these policy responses have in common that, sooner or later, questions about the effectiveness and potential side effects will be asked. In the aftermath of the financial crisis, one of the concerns regarding the policy responses was that higher capital requirements in particular for systemically important banks would lead to higher funding costs for these banks and their corporate clients and cause a contraction in lending. Today, the fiscal measures taken by governments are crucial to support companies, protect jobs, stabilise demand and reduce uncertainty. But they may, over time, also have potentially negative side effects in terms of debt sustainability and blurring the lines between private and public sector activity.

In such situations, structured policy evaluations can help to assess both the effects and the potential side effects of policy measures. Policy evaluation provides useful input for the decision-making processes, and it is an important element of public sector accountability and transparency. In the context of post-crisis financial sector reforms, the Financial Stability Board (FSB) has taken the lead in this regard. In 2017, it developed a structured framework for policy evaluation. Since then, four evaluations have been conducted.

Evaluating post-crisis financial sector reforms: The FSB framework

The period prior to the Global Crisis was characterised by a strong expansion of globally active banks across borders. Macroeconomic conditions were benign. With hindsight, we know that beneath the surface, severe tensions had been building up. The degree of systemic risk in the financial system was underestimated while the resilience of financial intermediaries was overestimated. The fault lines of the global financial system erupted with the crisis – with severe economic, social, and political consequences.

Policymakers acted swiftly in response to the crisis. At the Pittsburgh summit in 2009, G20 leaders decided on a package of reforms and a regular monitoring of implementation. The core objective of the reforms was to reduce the likelihood and severity – and associated public cost – of future financial crises (FSB 2019a).

Monitoring the implementation of these measures at the national level, surveillance of relevant emerging risks, and coordinating appropriate policy responses globally is the task of the FSB. The FSB was established in 2009 as a successor of the Financial Stability Forum. Today, its membership comprises 65 institutions representing 25 jurisdictions.

With the main elements of the post-crisis reforms agreed and implementation of core reforms underway, initial analysis of the effects of these reforms became possible. To that end, the FSB developed a framework for the post-implementation evaluation of the effects of the G20 financial regulatory reforms (FSB 2017). The framework guides analyses of whether reforms are achieving their intended outcomes and helps to identify any material unintended consequences that may have to be addressed, without compromising on the objectives of the reforms. It sets a common framework for the evaluation of policies, but it does not change the responsibility or remit of national policymakers or international standard setting bodies.

The FSB has so far completed three evaluation projects. The first dealt with reforms of derivatives markets, which aimed at reducing complexity and improving transparency and standardisation in derivatives markets (FSB 2018a). Results suggest that, overall, reforms are achieving their goals. Two further evaluations assessed the implications of the reforms for the financing of infrastructure projects (FSB 2018b) and for the financing of small and medium-sized enterprises (SMEs) (FSB 2019b). Neither finds material and persistent negative effects on financing conditions. If anything, banks with more binding capital requirements lend less, but aggregate lending is not affected.

Evaluation of TBTF reforms

In an ongoing evaluation, FSB members assess the effects of the ‘too-big-to-fail’ (TBTF) reforms. Results of this evaluation have been published in a consultation report in June 2020, and the consultation closes at the end of September 2020 (FSB 2020).

The evaluation examines the extent to which TBTF reforms for systemically important banks that have been implemented to date are achieving their intended objectives. It assesses whether the reforms are reducing the systemic and moral hazard risks associated with systemically important banks. Because these risks cannot be observed directly, the evaluation focuses on the relevant underlying mechanisms and associated indicators: decisions of banks concerning their funding and balance sheets structures that have implications for systemic risks; the feasibility of triggering resolution policies for the public authorities; and the assessment of market participants concerning the credibility of resolution, which affects banks’ funding costs.

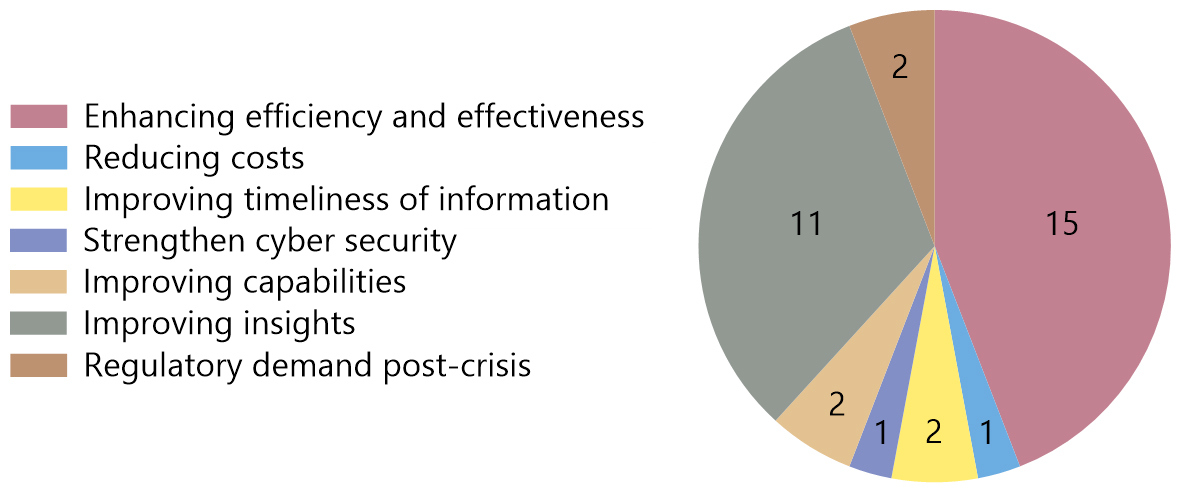

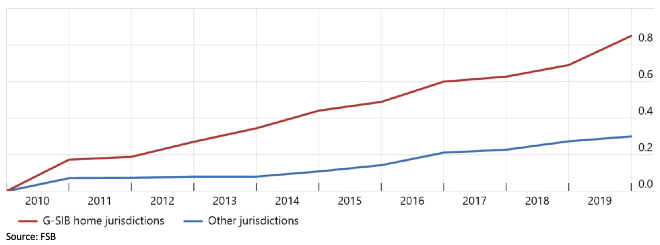

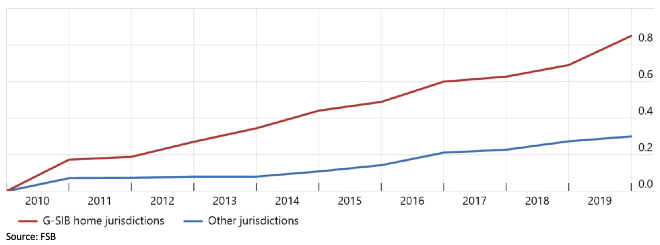

The ability of authorities to resolve systemically important institutes in an orderly manner without exposing taxpayers to losses, while also maintaining continuity of their vital economic functions, is a key element of these reforms. Countries have made significant progress in implementing resolution reforms (Figure 1), and it remains important to continue implementing missing reform elements. The feasibility and credibility of resolution policies do not only matter in times of distress. Rather, credible resolution frameworks shape the incentives of banks and the risk assessment of market participants already during the lifetime of these institutions.

Figure 1: Average resolution reform index for G-SIB home jurisdictions and other jurisdictions

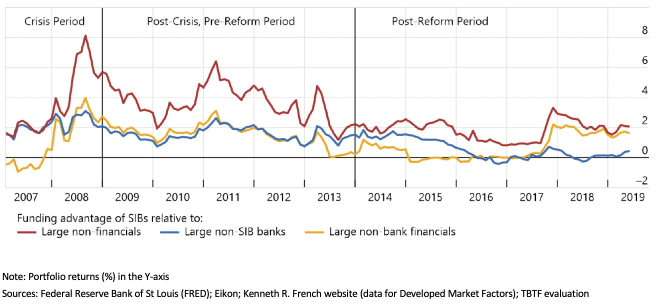

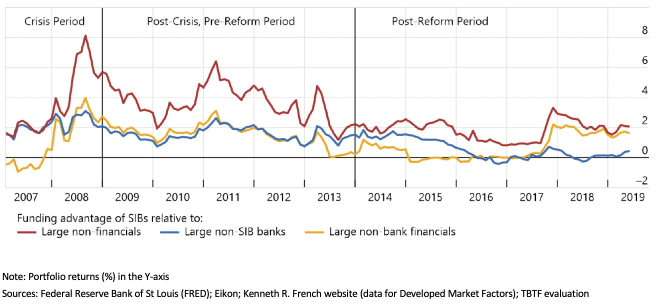

The evaluation report shows that indicators of systemic risk and moral hazard have fallen. Systemically important banks are much better capitalised and have built up significant loss-absorbing capacity. Improvements in capitalisation, lower risks, and higher funding costs have contributed to lower return on equity of systemically important institutions, which is consistent with higher resilience. Indeed, funding cost advantages of systemically important banks have fallen (Figure 2), and funding costs now appear to reflect the probability of a bail-in in the event of failure.

Figure 2: Funding cost advantage of systemically important banks

Going beyond the incentives of individual banks, the evaluation examines the broader effects of the reforms on the financial system. This includes overall financial system resilience and structure, the functioning of financial markets, global financial integration, or the cost and availability of financing. The evaluation shows that effective TBTF reforms bring net benefits to society. Not only are banks more resilient, there are also no signs of material negative side effects. In particular, there has been no reduction in the aggregate supply of credit to the real economy.

However, there are still gaps that need to be addressed. Some obstacles to resolvability remain, and there are gaps in information available to market participants and public authorities. For example, gaps remain with regard to TLAC implementation, funding in resolution, and the valuation of bank assets in resolution. Enhancing disclosures of information relating to the operation of resolution frameworks; the resolvability of SIBs, including TLAC, may help market participants better understand how resolution will work and to assess or price the risks. Public authorities may benefit from enhanced information on who owns TLAC issued by G-SIBs, which is needed to assess the potential impact of a bail-in on the financial system and the economy. Overall, steps taken in this direction can help improve the credibility of resolution regimes.

Lessons for the COVID-19 pandemic

Post-crisis financial sector reforms proved to be highly valuable in the light of the outbreak of the COVID-19 pandemic. Many firms in the non-financial sector have been severely affected by the corona shock and would not have survived without quick and decisive policy interventions across jurisdictions. This downturn of the real economy poses a threat to the financial system. The financial sector reforms implemented as a reaction to the Global Crisis contributed to making the global financial system more resilient, particularly in light of a shock that originated outside the financial sector. Should distress in the financial system materialise, authorities now also have more resolution tools at their disposal to deal with it.

However, the pandemic is still evolving, and the path to recovery remains highly uncertain. Developing common and strong policy responses, encouraging their coherent implementation, and monitoring their efficacy remains crucial.

Policy evaluation is key to ensuring transparency and accountability to the general public. When the post-crisis financial sector reforms were launched more than ten years ago, there was widespread concern that higher capital requirements might lead to a decline in lending to the real economy. Evaluations have shown that this has not been the case, but they also show room for improvements in the current regulatory system. Similarly, policymakers will be confronted with discussions on the effects and potentially negative side effects of the decisions taken to shield the economy from the adverse effects of the COVID-19 pandemic.

Notwithstanding the differences between the Global Crisis and the COVID-19 pandemic, there are broader lessons that can be drawn for policy evaluations in terms of independence and infrastructure.

Independence and transparency are crucial factors for the credibility of policy evaluations. Members of the FSB have been involved in the design of the policies that they are evaluating. As one cannot grade one’s own homework, transparency and stakeholder engagement are thus key (Quarles 2019). The FSB evaluations ensure stakeholder engagement along several dimensions. Academic advisors, who are leading experts in their field, support the FSB working groups. Workshops are organised, bringing together relevant stakeholders of the financial sector in order to solicit their views. Before publishing the final version of the evaluations, a public consultation enables stakeholders to provide fundamental feedback on the evaluation.

Infrastructure for policy evaluations is another important element of an evaluation process. Policy evaluations based on scientific methods and evidence are time consuming, require the input of high-quality data, and an established protocol. The general evaluation framework that the FSB developed in 2017 has provided the analytical and procedural basis for the evaluations that followed. Another core element of an evaluation infrastructure is the availability and access to sufficiently detailed, often granular, data. Finally, evaluations need to draw on existing studies and literature. Repositories of evaluation studies which provide ready access to such literature are thus a core element of an evaluation infrastructure. For instance, the BIS established FRAME (Financial Regulation Assessment: Meta Exercise), an online repository of studies on the effects of financial regulations. From October 2020 onward, this repository will also include information on the TBTF reforms.

Conclusion

The COVID-19 pandemic requires policy responses that are unprecedented and reach a global scale. This column argues that there are important lessons to be learned from the policy response to the Global Crisis. The first lesson concerns the preparedness of the global financial system. An on-going evaluation of too-big-to-fail reforms shows that the global banking system has been more resilient at the onset of the COVID-19 pandemic. Also, thanks to the reforms, policymakers have better tools at their disposal to deal with distress in the financial sector. The second lesson concerns the importance of structured policy evaluations for the accountability and transparency of policy responses to global crises. Such evaluations require good infrastructure, including a structured evaluation framework and data infrastructure.

References

FSB (2017), “Framework for Post-Implementation Evaluation of the Effects of the G20 Financial Regulatory Reforms”, Financial Stability Board, Basel.

FSB (2018a), “Incentives to centrally clear over-the-counter (OTC) derivatives – A post-implementation evaluation of the effects of the G20 financial regulatory reforms – final report”, Financial Stability Board, Basel.

FSB (2018b), “Evaluation of the effects of financial regulatory reforms on infrastructure finance”, Financial Stability Board, Basel.

FSB (2019a), “Progress in implementation of G20 financial regulatory reforms – Summary progress report to the G20 as of June 2019”, Financial Stability Board.

FSB (2019b), “Evaluation of the effects of financial regulatory reforms on small and medium-sized enterprise (SME) financing”, Financial Stability Board, Basel.

FSB (2020), “Evaluation of the effects of too-big-to-fail reforms: consultation report”, Financial Stability Board, Basel.

Quarles, R K (2019), “Ideas of Order: Charting a Course for the Financial Stability Board”, Speech at the Bank for International Settlements – Special Governors Meeting, Hong Kong, 10 February.

Rodrik, D (2019), “Putting Global Governance in its Place”, NBER Working Paper 26213.

Endnotes