Press enquiries:

+41 61 280 8477

[email protected]

Ref: 1/2026

- Annual Resolution Report highlights the FSB’s ongoing efforts to strengthen the global resolution regimes for banks, insurers and financial market infrastructures.

- The FSB will undertake further work to support members addressing critical challenges, such as funding in resolution and effective bail-in execution, particularly in cross-border contexts.

- The FSB is planning to launch a strategic review of its crisis preparedness activities to ensure that they remain well aligned with emerging risks and changes in the financial sector.

The Financial Stability Board (FSB) today published its 2025 Resolution Report, which reviews global progress in implementing resolution reforms and enhancing crisis preparedness across the financial sector. The report also sets out the FSB’s priorities for 2026 to advance the operationalisation of resolution frameworks.

Foundational resolution frameworks are now mostly in place, with significant progress in operational planning and resolvability assessments.

In 2025, the FSB focused on supporting resolution authorities’ operational readiness by publishing a practices paper on transfer tools, which shares insights and draws lessons from past resolution cases. The FSB also supported knowledge sharing on funding in resolution and advanced work on bail-in execution by forming a dedicated task force. Additionally, the FSB published draft guidance to promote consistency in determining which insurers should be subject to recovery and resolution planning requirements.

Dominique Laboureix, Chair of the Single Resolution Board, and Chair of the FSB Resolution Steering Group, said “This Resolution Report highlights the progress achieved in 2025 in enhancing crisis readiness across banks, insurers and CCPs. In 2026, we will build on this momentum, focusing on removing remaining challenges to cross-border bail-in execution and funding in resolution, and advancing cross-sector information sharing and collaboration to further strengthen global financial stability.”

Looking ahead, the FSB plans to conduct a peer review on public sector backstop funding mechanisms and to publish a practices paper on funding in resolution to further support operational planning. The FSB is also planning to launch a strategic review of its crisis preparedness activities. The review will aim to ensure the FSB’s crisis preparedness activities reflect emerging vulnerabilities and structural changes in the financial system as well as to strengthen coordination among the FSB and standard-setting bodies with crisis preparedness mandates.

The FSB has also published an update to the Good Practices for Crisis Management Groups, which was first issued in 2021. The supplementary information aims to enhance crisis coordination between home and host authorities outside of crisis management groups.

Notes to editors

The 2025 Resolution Report has been prepared by the FSB Resolution Steering Group, which is the primary global forum for the development of global standards and guidance on resolution regimes and recovery and resolution planning for systemically important financial institutions. ReSG is chaired by Dominique Laboureix, Chair of the Single Resolution Board.

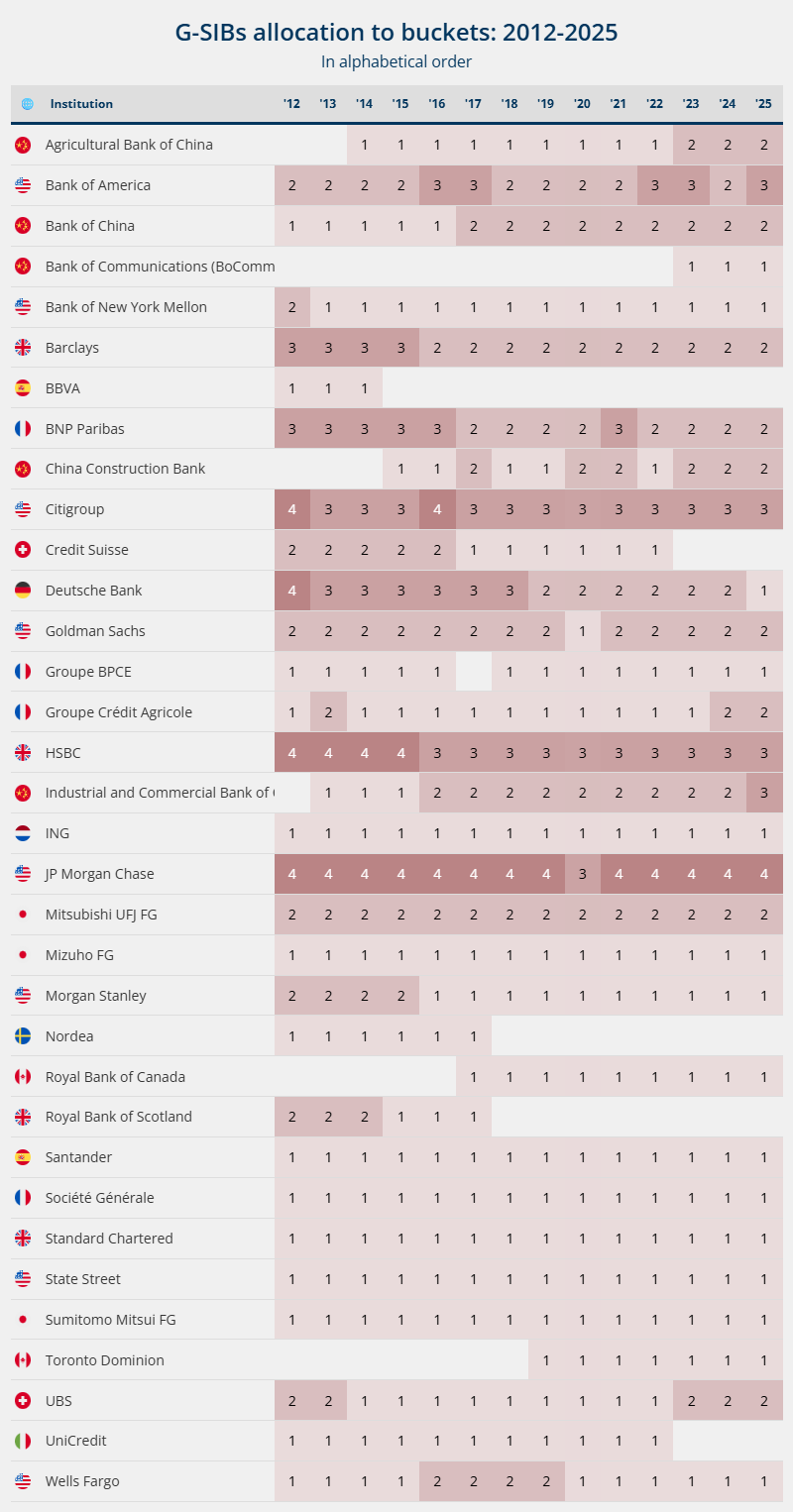

Crisis Management Groups of global systemically important banks (G-SIBs) have been in place for over 10 years as a core part of the post global financial crisis coordination infrastructure. According to the FSB’s Key Attributes of Effective Resolution Regimes for Financial Institutions Key Attribute 8, home and key host authorities of all G-SIBs should maintain CMGs to enhance preparedness and facilitate the management and resolution of cross-border financial crises.

The FSB coordinates at the international level the work of national financial authorities and international standard-setting bodies and develops and promotes the implementation of effective regulatory, supervisory, and other financial sector policies in the interest of financial stability. It brings together national authorities responsible for financial stability in 24 countries and jurisdictions, international financial institutions, sector-specific international groupings of regulators and supervisors, and committees of central bank experts. The FSB also conducts outreach with approximately 70 other jurisdictions through its six Regional Consultative Groups.

The FSB is chaired by Andrew Bailey, Governor of the Bank of England. The FSB Secretariat is located in Basel, Switzerland and hosted by the Bank for International Settlements.